14 January 2016

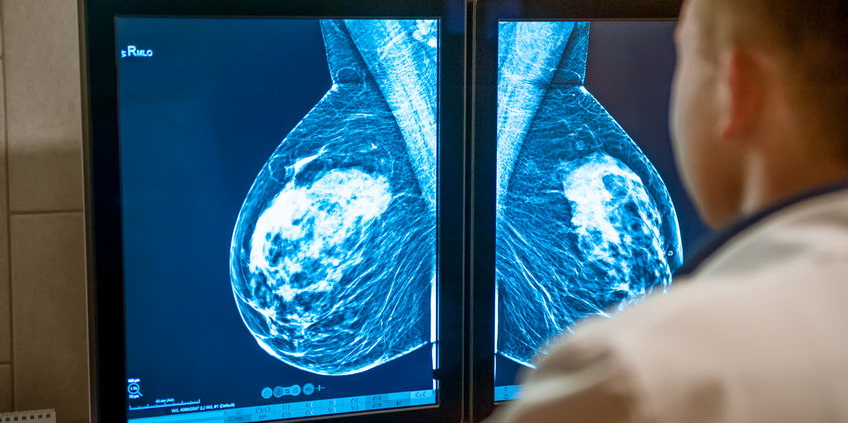

Does cancer screening save lives? A study published in the British Medical Journal study noted that while many studies of cancer screenings report decreased cancer-specific mortality rates, the benchmark should be overall mortality rates, and this has not been consistently demonstrated. The 15 minute podcast is worth a listen. The lead author, Dr. Vinay Prasad, is not arguing against screening for cancers, but he notes that screening is for healthy people, who in general care about living longer and better, but disease-specific mortality does not capture that. He feels that before you tell a person that a screening test “saves lives”, you should be able to prove that the screening test and subsequent early detection results in an improvement in overall survival, not just disease-free survival.

It’s an interesting concept, and he goes on to note that the public (and physicians) have an inflated view of what screening can do for them. In addition, physicians sometimes get into a “check box” mentality – screening is just another thing to check off the list, or refer a patient for, when we really should be having discussions about the risks and benefits of screening and embracing the shared decision making process. He also noted that physicians need to be comfortable when patients make choices that are right for them, but might not be in line with the MD recommendation. He concluded by stating ” We encourage healthcare providers to be frank about the limitations of screening—the harms of screening are certain, but the benefits in overall mortality are not. Declining screening may be a reasonable and prudent choice for many people”. He also quoted Dr. Otis Brawley, chief scientific and medical officer of the American Cancer Society, who has stated: “We must be honest about what we know, what we don’t know, and what we simply believe”.

Personally, I feel that screening for certain cancers such as breast and colorectal cancer is of benefit even if there is improvement only in disease specific, and not overall, survival. But this is a decision that each person needs to make for themselves, ideally with input from their physician, taking into account the potential harms of screening (overdiagnosis / overtreatment with the subsequent impact on quality of life, as well as potential complications of the screening test itself) and the potential benefits.

Reuters coverage of BMJ Study

Medscape coverage of BMJ Study

Medscape – In Cancer Screening, Why Not Tell the Truth?