16 August 2020

As part of the pathologist’s evaluation of a breast cancer, the presence or absence of the estrogen and progesterone receptor (ER/PR) and level of Her2/neu gene expression is determined. These are important factors used to help guide treatment recommendations for endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, and Her2-targeted therapy.

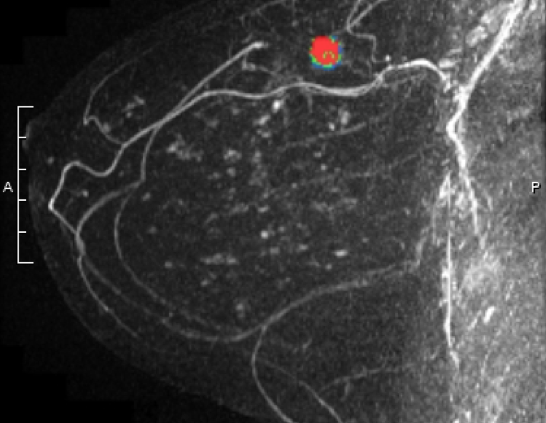

If metastatic breast cancer develops (when the primary tumor spreads to other areas of the body, such as the lungs, liver, bone, or brain), it is recommended that ER/PR and Her2/neu testing be performed on the metastatic cancer. It is known that cancers can sometimes mutate and the metastatic lesion may have different characteristics compared with the primary lesion. While current international guidelines do recommend biopsy of the metastatic tumor, this is not always performed.

A study recently published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment reported on discordance between the primary and metastatic breast cancer. The study was performed in Germany. Among patients treated for breast cancer between 1982 – 2018, 541 had receptor status from both the primary and the metastatic breast cancer documented in the medical record.

The researchers found that there was a 14% discordant rate for ER, a 32% discordant rate for PR, and a 15% discordant rate for Her2/neu. All of these were felt to be clinically meaningful, in that a change in ER/PR or Her2/neu status would result in a change in treatment recommendations. If a tumor loses the ER/PR receptor, endocrine therapy (such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors) would be ineffective. If a tumor gains the Her2 protein, Her2-targeted therapy should be instituted.

They noted several reasons for discordance including:

- Variability in the testing process, especially as testing procedures have changed over time

- Tumor heterogeneity – cancers may not be made up of a single cell “clone”

- Mutation of the tumor over time

Median follow up was 58 months. They noted that loss of ER/PR positivity was associated with worse overall survival, and gain in Her2 positivity was associated with improved overall survival. However, one limitation of the study is that they could not determine if the survival differences were actually due to the changes in the tumor and subsequent treatment. They noted other limitations of the study including that the dataset included patients with Her2 positive disease who were treated prior to the approval of trastuzumab (Herceptin), there were changes in cut-off values for what was considered ER/PR “positive” during the study period, and receptors were not re-checked in a centralized lab.

However, despite the limitations, it is important to note that treatment recommendations could be altered as a result of testing the metastatic cancer. The researchers concluded that “Where feasible, metastatic lesions should be biopsied in accordance with current guidelines.” If you have been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, it is important to discuss biopsy of the metastatic tumor with your oncologist, and not assume that it is the same cell type as the primary lesion. This study found that in at least 14% of cases, knowledge of the metastatic tumor biology could alter treatment recommendations.