23 November 2014

Guest Post by Dr. Oliver Bogler

When thinking about a post on male breast cancer, one person came to mind – Dr. Oliver Bogler. As a cancer researcher, Dr. Bogler has a very unique perspective on his diagnosis, treatment, and the larger problem of research disparities when it comes to male breast cancer. Here is his guest post:

My personal encounter with breast cancer started with my diagnosis in September of 2012. My story is very typical. As I have written more extensively about it elsewhere let me be brief: I felt a lump, and after a few months of denial I had it checked out, and then very quickly was diagnosed and treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where I also work. More on that below, but let’s first look at some facts about the male disease.

About Male Breast Cancer

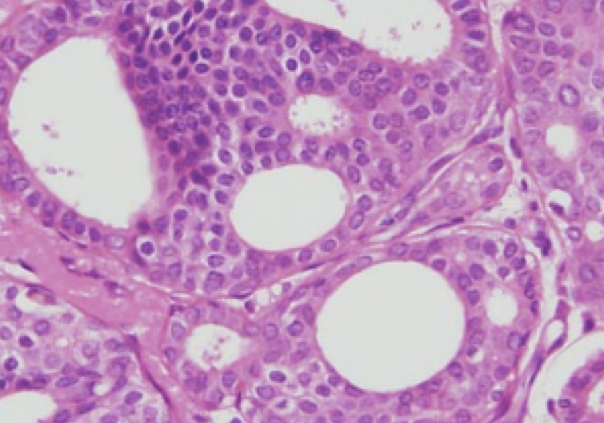

Approximately one in every hundred people diagnosed with breast cancer is a man. That’s about 2,200 new cases a year in the USA. Men have breasts, meaning that they have the same lobular glands and ducts that women have, though they have less tissue and it does not produce milk. Accordingly, male breast cancer is typically ductal carcinoma and hormone receptor positive and Her2 negative, which is also the most common type of breast cancer in women. Men are diagnosed later in life, typically, with a median age at diagnosis of 68, or about 7years older than women. For that reason men also present more often with more advanced forms of breast cancer – stages III and IV are more common, and stage I very rare. One possible explanation is that a lack of awareness results in delayed diagnosis, and so more advanced presentation at a later age.

Treatment regimens for men are essentially identical to those used for women, and outcomes are very similar, as far as we know. Because male breast cancers are typically hormone receptor positive, hormone therapy with the anti-estrogen tamoxifen is commonly an important part of the therapy. It suppresses male estrogen, and thereby other hormones also, which are co-regulated, including testosterone.

Many websites, including those of the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute provide fundamental information about male breast cancer. Interventional clinical trials on breast cancer that men are eligible for can be found here (ClinicalTrials.gov is a registry and results database of publicly and privately supported clinical studies of human participants conducted around the world).

My advice: if you feel a lump, any lump, go see a doctor right away.

My Journey – Our Journey

One of the reasons I hesitated to get my lump checked out was that my wife had been diagnosed and treated for breast cancer about 5 years before me. I couldn’t really grasp the improbability of it hitting our nuclear family twice. Being Irene’s care taker and then a patient allows me to say with confidence that the treatments for men and women are identical: we both had up-front chemotherapy in a two step regimen: 12 rounds of weekly Taxol and then 4 rounds of the combination FAC at three week intervals. MD Anderson physicians prefer to give the chemo first as it provides an opportunity to see how the tumor responds. Then we both had surgery – modified radical mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection – followed by 6 weeks of radiation to the chest wall. Now we both take hormone therapy – aromatase inhibitors for Irene, good old tamoxifen for me. Evidently we feel that marriage is all about sharing experiences 🙂

What we know about male breast cancer and opportunities to learn more

What do we know? Probably not enough. I do accept that the treatment men receive is effective – there are some relatively small-scale, hospital registry based studies showing this. When adjusted for age and stage at diagnosis, it looks like men do as well as women with today’s approaches. On the other hand, the possibility that a sex-hormone driven cancer may have important differences between men and women cannot be excluded. Very encouraging is a current, larger registry trial in a network of European and US cancer centers with about 1,200 men that will provide a robust baseline outcomes data set and afford the opportunity to collect tissue and study the disease. It is the kind of research that was being done 20+ years ago in women.

An analysis I wrote about on my blog and in Breast Diseases Quarterly [Bogler, O. (2013) Male Breast Cancer: Opportunities for Research and Clinical Trials. Breast Diseases: A Year Book Quarterly 24(3), 216-218] suggests that there is very little primary research on the male disease. There are no laboratory models, cell lines or other tools. Few if any grants supporting this kind of fundamental biology are in evidence, and aside from the inclusion of male breast cancer in the epidemiology of rare cancers it is hard to find any support for research from the National Cancer Institute or foundations. Given that the NCI alone spends $600M on breast cancer research, there is in my mind ample opportunity to dedicate some to this question. Perhaps 1% would be a good start?

On a similar note, men are only eligible for about 30% of breast cancer clinical trials found on clinicaltrials.gov, suggesting that access is a real issue. Of course in some instances our inclusion may not make sense, but I believe that in many instances inertia rather than a biological rationale underlies the exclusion of men. Both of these areas provide significant opportunities to learn more about the male disease and how best to deal with it clinically.

The Awareness Gap

Being a man with what is widely understood to be a women’s cancer leads to some dissonant experiences. To me these are mostly mildly funny, and not an issue – being asked how I get a mammogram for instance (the same way you do…), or filling out a form that asks me whether I am pregnant or when my last period was. Its fine – I get it. Mostly women here, and mostly the men in the waiting room aren’t wearing the medical arm band. But having breast cancer as a man is still (local) news worthy, and has modest shock value – that is surprising. The issue here is that a lack of awareness is probably a contributing factor to the delayed diagnosis in men and that means in some cases in their earlier death. It is certainly contributing to the underfunding of research and exclusion of men from trials. We need to change that.

A key challenge for men with breast cancer is the phenomenal success of the breast cancer awareness community. While the excesses of “pink” are unfortunately common these days, I do acknowledge the amazing work the community has done, and am deeply grateful for it. Alone the fact that we can have frank, open discourse about breast cancer, any cancer, is a tribute to the brave women who came out with their disease in the past 50 years. Then, the mobilization of public and private resources for awareness, screening and research is a tremendous accomplishment. And the US is a clear leader in this – a significant cultural accomplishment. But if this huge silver lining has a tiny, tiny black cloud it is that pink leaves almost no room for awareness about men. Breast cancer actually is not a sex-specific cancer like ovarian, uterine, testicular or prostate – it just appears to be. A great illustration of this phenomenon for me is the NFL players who in October don pink in support of women with breast cancer (hurray!) and completely fail to take the opportunity to also mention that they themselves could be diagnosed with this disease one day (booo!).

I want to close by being clear: I am not advocating for male breast cancer at the expense of other forms of breast cancer. Not at all. I want it to have its place with, and alongside. And in proportion – 1% would be a good start. Perhaps my concerns are not dissimilar from those of the inflammatory, triple negative or metastatic breast cancer communities: being outside the pink mainstream presents awareness challenges, which in turn make it harder to gain the resources needed to change the fate of many women and men with breast cancer.

Dr. Oliver Bogler is a cancer researcher, male breast cancer patient, and male breast cancer advocate. His blog can be found at Entering a World of Pink.

Dr. Oliver Bogler is a cancer researcher, male breast cancer patient, and male breast cancer advocate. His blog can be found at Entering a World of Pink.