30 June 2019

Note – if you would like a copy of the studies discussed below but are not able to access them from the journal website, please email me: contact at drattai dot com

In a study recently published in the Annals of Surgical Oncology, Bateni et al used the National Cancer Database to assess outcomes in patients with male breast cancer based on surgical therapy. The authors found improved 10-year survival in patients who underwent breast conserving therapy (BCT) which they defined as partial mastectomy (also called lumpectomy) plus radiation therapy.

Male breast cancer makes up about 1% of all new breast cancer diagnoses; approximately 2500 men are diagnosed in the US each year. Treatment guidelines for male breast cancer are similar to those for post-menopausal women despite growing evidence that breast cancer in men is a biologically different disease versus that in women. One of the challenges for clinical trials is the relatively small numbers of male breast cancer patients diagnosed each year. However, many clinical trials have not included men.

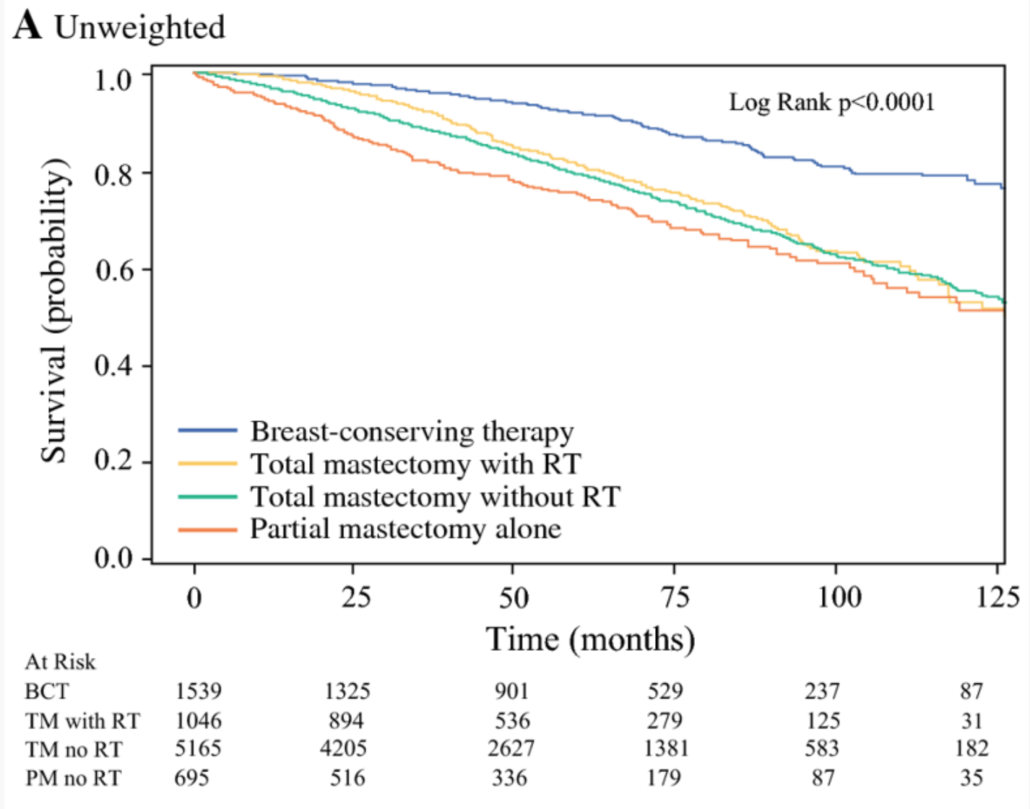

A total of 8445 patients with stage I and II breast cancer, treated between 2004-2014, were included for analysis. 61% underwent mastectomy, and 18% underwent BCT. 12% had mastectomy with radiation, and 8% had partial mastectomy without radiation. Median follow up was 52 months. At 10 years, overall survival was as follows:

- 74% BCT

- 58% mastectomy

- 56% mastectomy with radiation

- 56% partial mastectomy without radiation

The image below is Figure IA from the manuscript, which show the “crude” overall survival for male breast cancer patients depending on surgical therapy.

Evaluating patients who had breast conservation with or without radiation, the authors noted that patients who were older, had higher tumor stage, higher cellular grade, and triple negative histology had poorer overall survival rates. They noted that there were differences in patient age, co-morbidities (other medical conditions), margin status and chemotherapy use for patients who underwent BCT versus partial mastectomy alone. However, after accounting for these differences, survival rates still favored BCT, suggesting that radiation therapy is an important component of improved outcomes.

Limitations of the study noted by the authors include the retrospective nature, and the inability to understand some of the factors that influenced the decision for mastectomy versus breast conservation. Her2/neu status was not uniformly reported in the NCDB until 2010, so almost half of the patients in this study did not have this information. They also noted a larger percentage (4.9 vs 1.4%) of patients in the BCT group had triple negative breast cancer, which might explain why more of these patients were also treated with chemotherapy. It is also not clear how much of an influence the use of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy had in terms of the survival rates that were noted.

In a separate article, De La Cruz et al performed a systematic literature review of the studies evaluating breast conservation in men (excluding the Bateni et al study discussed above). The authors found 8 publications meeting their criteria. Among these studies, there were 859 patients who underwent breast conservation, 14.7% of all male breast cancer surgeries in the combined papers. Reporting on the “weighted average”, local recurrence (cancer returning in the breast) was 9.9%, disease-free survival was 85.6% and 5 year survival was 84.4%. As with the retrospective database analysis, there are limitations to this type of literature review – studies may use the same data points for inclusion, including use of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and margin status. There may be significant differences in the patient populations in the various studies reviewed. As in the Bateni et al paper, there may be multiple unknown factors that influenced a decision for surgery type.

Men tend to present with larger tumors, especially relative to breast size, so often mastectomy is recommended. However, the authors of both papers were of the opinion that breast conservation is oncologically safe and a very reasonable option for men with early stage breast cancer, if they desire. Bateni et al stressed the importance of radiation therapy if breast conservation is utilized. Both papers highlight the importance of clinical trials for male breast cancer, so that treatment recommendations can be based on the best available evidence.

Additional information on Male Breast Cancer: