15 January 2019

The US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) has released draft recommendations for the use of medications to reduce the risk of breast cancer development in women who are at increased risk. The draft document, which is open for public comment until February 11, 2019, is an update of their 2013 recommendation – the conclusions are similar, and the current document now includes aromatase inhibitors. The recommendations apply to women at high risk (see next 2 paragraphs) and do not apply to women with a current or previous diagnosis of invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Various factors are taken into account when assessing breast cancer risk. Family history is certainly important, but other factors such as age at first menstrual cycle, age at first pregnancy, and prior biopsies showing abnormal cellular changes (such as atypical hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ) and impact risk. Weight gain after menopause, breast density, and sedentary lifestyle also contribute to increased risk. Various risk assessment calculators can be used to estimate a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer. Unfortunately, risk assessment is not an exact science – we have a long way to go in terms of predicting whether an individual woman will or will not develop breast cancer.

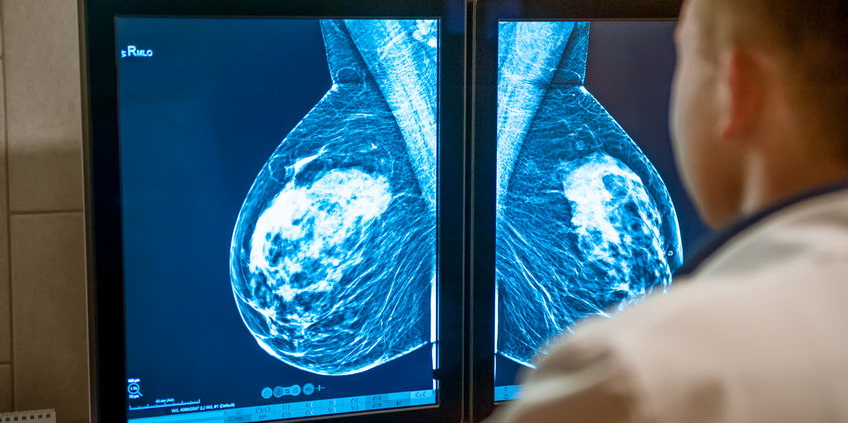

An “average” woman’s risk of developing breast cancer over 5 years is approximately 1.0 – 1.5%, and 8-12% over her lifetime. Women are considered to be “high risk” if their 5-year risk is greater than 1.7-(although the USPSTF uses 3%) and if the lifetime risk is 20% or greater. In these patients, we often utilize supplemental imaging such as MRI and/or ultrasound in addition to mammography, and these patients are candidates for taking risk-reducing medications. The medications used to reduce risk are also used for breast cancer treatment: tamoxifen, raloxifene, and the aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole).

The USPSTF reviewed available data and concluded with “moderate certainty” that there is a “moderate net benefit” from taking risk reducing medications in women who are at increased risk. In addition, they noted that the potential harms of the medications outweigh any potential benefit in women who are notat increased risk. As these medications either block the estrogen receptor in the breast (tamoxifen and raloxifene) or diminish estrogen production (aromatase inhibitors) they will only reduce the risk of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer.

Compared to placebo, tamoxifen reduces the likelihood of invasive breast cancer development by 7 events per 1000 women over 5 years. Raloxifene results in 9 per 1000 fewer invasive breast cancers, and aromatase inhibitors result in 16 per 1000 fewer invasive cancers. The benefit increases as a woman’s level of risk increases. Tamoxifen can be used in premenopausal women, but raloxifene and the aromatase inhibitors are only used in postmenopausal women. The report noted that aromatase inhibitors are primarily used to treat breast cancer, and are not currently FDA approved for risk reduction.

All of the medications have the potential for side effects, which the USPSTF considered to be “small to moderate”. Both tamoxifen and to a lesser extent, raloxifene, can increase the risk of blood clots – this risk is greater in older women. Tamoxifen can increase the risk of endometrial cancer and cataract development, and both medications can increase the likelihood of hot flashes. Both medications can reduce the risk of some types of fractures. Aromatase inhibitors can be associated with hot flashes, gastrointestinal symptoms, musculoskeletal pains, possible cardiovascular events (primarily stroke) and may increase fracture risk.

Most trials utilized the medications for 3-5 years for risk reduction. The report notes that the benefits of tamoxifen continue at least 8 years after discontinuation of therapy, and the risk of tamoxifen-associated blood clots and endometrial cancer return to baseline after treatment has ended. They noted insufficient data on length of protection for raloxifene or the aromatase inhibitors.

The USPSTF did identify research needs and gaps, including how to better identify individuals at increased risk, racial disparities, and that longer follow up of patients using raloxifene and aromatase inhibitors for risk reduction is needed. In addition, as there are multiple risk assessment models, more work needs to be done to determine which is “best” – different models may be more appropriate depending on specific clinical factors.

Not addressed in the USPSTF document is that fact that many patients who are at high risk, as well as those who have been diagnosed with breast cancer, discontinue medication early (or do not start at all) due to side effects. An abstract presented at the December SABCS conference compared 5mg of tamoxifen (usual dose is 20mg) to placebo in high risk woman and found similar reduction in breast cancer development with fewer side effects. Lower dosing could be one answer, but more effective mediations with fewer side effects would certainly be welcome by all.