3 August 2013

What’s in a name? In the case of cancer, there are myths, fears, and misinformation – more than perhaps any other illness.

Cancer encompasses hundreds of different diseases and each one is complex. Even women diagnosed with exactly the same “type” of breast cancer and who undergo the same treatment can have very different outcomes. Not all cancers are equal and not all cancers are lethal.

While early detection and treatment were once equated with improved survival, we now know that tumor biology (characteristics governing the behavior of spread and response to treatment) plays an extremely important role in the prognosis of an individual cancer. There is an increasing recognition that current screening tests, meant to diagnose cancer in the earliest stages, will often diagnose lesions that have minimal potential to become aggressive or lethal. As our screening technology improves, we are detecting more patients in early stages or with pre-cancerous conditions and we are treating those patients with surgery and other potentially toxic therapies.

In 2012, the National Cancer Institute convened a working group to “evaluate the problem of ‘overdiagnosis’ which occurs when tumors are detected that, if left unattended, would not become clinically apparent or cause death.” Unrecognized overdiagnosis, they stated, “generally leads to overtreatment”1.

The recommendations of this panel were recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment in Cancer, An Opportunity for Improvement. The authors provide five recommendations:

1. Physicians and patients alike need to acknowledge that screening results in overdiagnosis – especially in breast, lung, prostate and thyroid tumors.

2. The term ‘cancer’ should be reserved for describing lesions with a reasonable likelihood of lethal progression if left untreated.

3. Create observational registries for low malignant potential lesions in order to better understand prognosis and best treatment options.

4. Mitigate overdiagnosis with an ultimate goal of preferential detection of consequential cancer while avoiding detection of inconsequential disease.

5. Expand the concept of how to approach cancer progression by controlling the environment in which cancerous conditions arise.

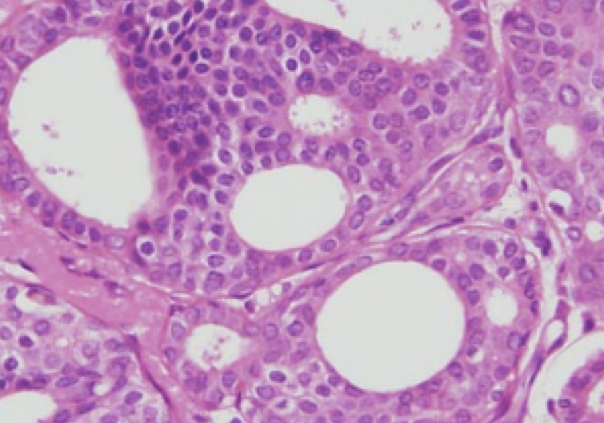

While these are certainly laudable goals, some important points should be made, especially in regards to breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in-situ – the most important being that we do not currently have biomarkers or other indicators that can clearly distinguish a potentially lethal cancer from a more indolent one. The field of cancer genomics is rapidly changing, and today more than ever, we can obtain very sophisticated prognostic information regarding an individual’s tumor. Despite that, Dr. Larry Norton, medical director of the Evelyn H. Lauder Breast Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, stated “Which cases of DCIS will turn into an aggressive cancer and which one’s won’t? I wish I knew that. We don’t have very accurate ways of looking at tissue and looking at tumors under the microscope and knowing with great certainty that it is a slow-growing cancer”2.

Regarding the modern management of DCIS, there are three points to remember:

1. When DCIS lesions diagnosed by needle core biopsy are surgically removed (which involves removal of substantially more tissue from the abnormal area), there is an approximately 15% rate of ‘upstaging’ to invasive ductal cancer 3. Put another way, one cannot always reliably predict the behavior of an entire lesion based on a core biopsy specimen.

2. During surgery for DCIS, axillary lymph node metastases have been demonstrated up to 20% of the time, usually indicating missed microinvasion or invasion 4.

3. Finally, if DCIS recurs, 50% of the time it is invasive 5.

What is important to be aware of is that any woman with breast disease, including DCIS, should be presented with the information necessary so that she may gain an understanding of where her diagnosis stands in the biological spectrum and the wide array of choices she has for treatment. DCIS is far from simple, and it is not to be taken lightly. Clearly there are cases where ‘watchful waiting’ is safe – but we cannot always reliably predict who will truly benefit from treatment. Moving forward, we need to be aware of the facts – what medical technology can provide the patient and the physician now, and we need to ask how we can drive this conversation in the future.

Deanna J. Attai, MD, FACS

Michael S. Cowher, MD