30 March 2015

Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2011, Featuring Incidence of Breast Cancer Subtypes by Race/Ethnicity, Poverty and State

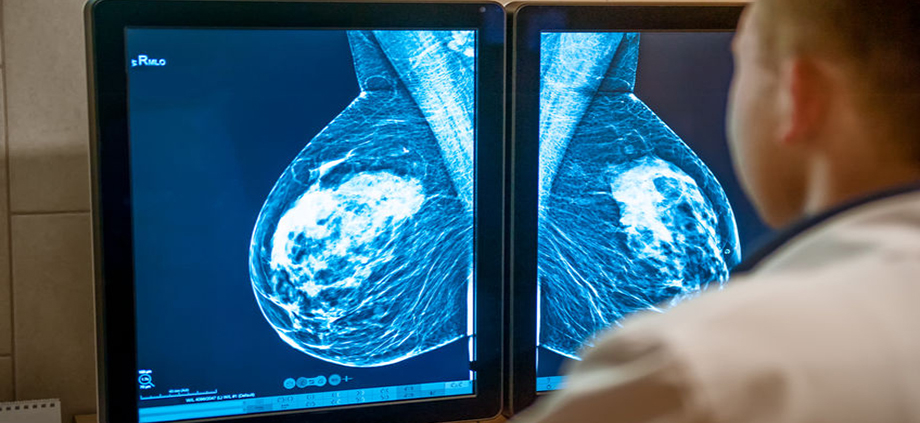

Today, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI) released a report reviewing cancer data, specifically breast cancer, from 1975-2011. For the first time, data regarding breast cancer subtypes was included in the report, and incidence of breast cancer subtypes by age, race/ethnicity, poverty level, and other factors are included. The following summarizes some of the information found in the report.

It is well known that breast cancer is not one disease. There are 4 primary molecular subtypes based on hormone receptor (HR) status (commonly reported as ER / estrogen receptor and PR / progesterone receptor) and Her2/neu status. The subtypes are:

– Luminal A: HR+ / Her2 negative; 72% of all breast cancers

– Luminal B: HR+ / Her2 positive; 10% of all breast cancers

– Her2-enriched: HR- / Her2 positive; 5% of all breast cancers

– Basal-like / Triple Negative: HR- / Her2 negative; 13% of all breast cancers

The report demonstrated that there are some unique patterns breast cancer subtype related to race/ethnicity, poverty level, and geography.

– HR+ / Her2- breast cancer is considered to be the least aggressive subtype. Rates of this subtype were highest in non-Hispanic white women. The rates of this breast cancer subtype decreased with increasing poverty levels for every racial and ethnic group. This subtype of breast cancer also correlated strongly with use of screening mammography.

– In women younger than age 45, HR+ / Her2 negative breast cancer rates are comparable among racial / ethnic groups, but for older women this subtype was seen more often in non-Hispanic white women.

– Non-Hispanic Black women had the highest rate of HR- / Her2 – (triple negative) breast cancer, which has been known for some time. However, as triple negative breast cancer is less common than HR+ / Her2 negative disease, more women had the latter subtype. The report also confirmed that this population had the highest rates of late-stage disease and of poorly differentiated pathology (indicates more aggressive tumor behavior) regardless of molecular subtype, and the highest rate of breast cancer deaths.

Overall trends in incidence and death rates from cancers were also noted in the report. Lung cancer remains the leading cause of death among both men and women. Black men had the highest cancer death rate of any racial or ethnic group. Lung, prostate and colorectal cancers were the leading causes of cancer death among men except in the Asian / Pacific Islander group where the leading causes were lung, liver and colorectal cancer.

Among women, the leading causes of death were found to be lung, breast and colorectal cancers. For both men and women, death rates for the 3 most common cancers declined. Exceptions were American Indian / Alaska Native men, lung cancer in Asian / Pacific Islander women (stable death rate) and colorectal cancer in American Indian / Alaska Native women (stable death rate). Death rates for liver, pancreatic, soft tissue and uterine cancers as well as melanoma were also reported. There are racial / ethnic differences present for these types of cancer as well.

There are many factors contributing to cancer incidence and death rates including race / ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographic location and more. Reporting cancer incidence by subtype will give more insight into population-based factors, and will hopefully lead to innovative solutions to the growing problem of disparities in cancer incidence and outcome.

Additional information from the National Cancer Institute.